- KINGDOM OF THE ICE BEAR -

|

| |

So wrote an early explorer of the group of islands known as Svalbard. Placed as they are some 3,000 kilometres north of London and only 1,200 kilometres from the North Pole, the coast is indeed cold, the sea frozen for all but four months of the year.

I was there in the winter of 1984 and this recent cold snap in the UK reminds me of the hardship we had to face in the hope of filming polar bears as they emerged from their winter dens. As I write this blog in Dorset, it’s just two degrees below freezing but when filming in Svalbard, we faced daily temperatures of down to minus 37ºC, plus the wind chill of course. It. Was. Cold.

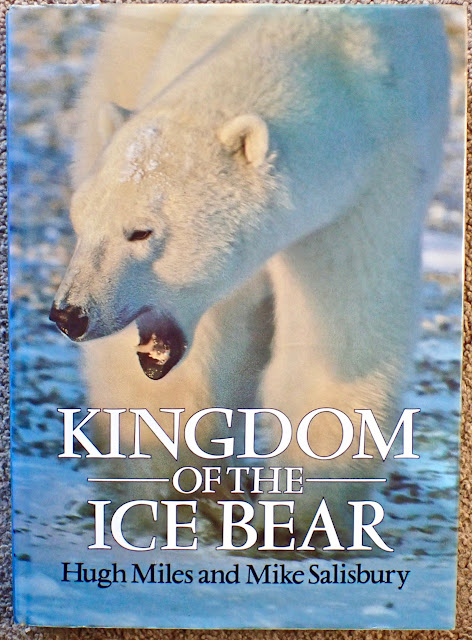

Our team of four included BBC Producer Mike Salisbury and we wrote a book about our two Arctic years and the seventeen expeditions we made to the far north when making a series of three one hour wildlfie films for the BBC, so I’ll use some excerpts from the book:

‘Mike and I are alone, surrounded by a frozen world in which humans become totally insignificant. The awesome expanse of landscape and sky merge into blankness, the complete horizon lost in a white infinity. From this spot there is nothing but ice and snow, all the way to the North Pole.’

Our challenge was to film the Arctic’s most charismatic animal at its most critical time of their year, our chapter heading illustrated by this delightful Inuit art: “Island of the Waking Bears”.

‘It was 4th March 1984 when we were just setting off on a six-week expedition, but just as we left Svalbard’s capital, Longyearbyan, our overloaded sledge overturned on a steep snow bank. Our wilderness adventure was of great interest to the local residents, so they had come to wave us off but, I suspect, now thought we wouldn’t make it. They were driving trucks, we four were on skidoos, dragging seven sledges between us, heading for the distant island of Edgeoya, some 200 kilometres to the east over a glacier and then frozen sea ice. We had only travelled one kilometre, so the possibility that we wouldn’t make it crossed our minds too!

We were in no doubt of the risks of the trip, both financial and physical, for the conditions would be unrelentingly harsh and we might not even be able to cross the sea ice with our heavy sledges. When and if we reached the island, we would then have to find an active polar bear den with cubs, and that is nearly always difficult.

Our companions on the expedition, Norwegian scientists Rasmus and Birger described the problem. ‘Female polar bears leave the sea ice in the autumn and head inland, finding a suitable snow bank high up in the mountains, They then dig out a den and let the snow blow over the entrance, sealing themselves in against the intense cold. Having been mated by a male out on the summer ice, the females give birth to one or two cubs at about Christmas. They nurse them until the weak sun appears, then, responding to the light, break open the den and within days, lead the cubs down from the mountains and out onto the sea ice to hunt for seals.’

It was this brief period of activity, when the female breaks out of the den with her cubs that was vital to our story of the Arctic but it’s one of the most difficult of any wildlife sequence in the world, so the four of us had everything we needed to film and survive for six weeks, including as much fuel as we could carry. We would be totally isolated from other humans. Our sledges, but not our minds, groaned under the burden.

We righted the overturned sledge and motored on, for it was the 4th March and an important day, the first time the sun had climbed above the horizon for 110 days. It’s appearance over the sea ice struck us as a symbol of hope - spring was on the way.

Travelling by skidoo, wrapped in numerous layers of clothes, masked against the frosty wind, deafened by the roar of the engine, the mind becomes isolated from your fellow travellers. However, on reflection, I know we were all feeling the same - a sense of anticipation, excitement, adventure, a little overawed and apprehensive perhaps, but, even though it was -28 degrees C and darkness was falling, we all felt lucky to be there.

The valley headed east, up into the mountains but our problems didn’t start until we reached the glacier that lay across our path. The twilight of night was upon us and the next three hours proved to be a sweaty struggle. We floundered in deep snow, man hauled loads, righted overturned sledges, burnt out drive belts on the skidoos, looped back and forth to drag the sledges over the pass, roped them through narrow gaps in the moraines and over the mountain top, all in polar darkness, but, largely unscathed, we made it to the far side and all that ‘Scott of Antarctica’ stuff certainly kept us warm.

Once over the glacier it was plain sailing, though it was several hours before we found the little trappers cabin in the blackness of the night, lit up by our headlights. The hut lay on the edge of the frozen sea but there was little to see, for snow drifts obliterated all but the roof. Once we’d dug our way in, the little stove lit, food simmering and sleeping bags laid out it made a cosy roost and for a first night in this beautiful country, it was memorable. We unpacked the sledges under the glorious glow of the Aurora Borealis, the atmospheric flares streaking and shimmering from one horizon to the other, drifting across the midnight stars. The Aurora was brighter than the moon and we stood enthralled in the icy air - sleep came easily that night.

After the days of planning, preparation and travel we woke reluctantly. We had been warm in our sleeping bags but were pleased it had been a cold night, for we hoped the sea ice we had to cross was frozen solid.

Just as we headed out towards our filming location of Edgeoya we were seen by our first bear, a big male who came across the ice to check us out. Before we could release the camera from the sledge, he took fright and ran off, a disappointment - and a relief, for we were still tuned to the streets of home and with our heads full of the stories of aggressive killer bears, we were not ready for a full on confrontation. It was good to see that at least one bear was afraid of humans.

Full of optimism, we headed due east, but after five kilometres were confronted by an impenetrable jumble of broken ice, before finding a gap in the ice that had only just refrozen and was too dangerous to cross. We motored back and forth but failed to find a safe way through this tortured landscape, so headed back to shore when darkness threatened and set up our tents on the sea ice, the only flattish place around. As we did so we saw five more bears and carefully set up the trip-wire system around the tents and sledges.

The theory is that when a bear comes to investigate in the night, the trip-wire sets off a thunder flash. This frightens the bear - and wakes us up - so if the bear returns, we would be able to defend ourselves. It’s important to remember the trip-wire is armed when leaving the tent in the dark for a pee, because once tripped, you have to shout to your trigger happy colleagues not to shoot!

However, that night was extremely cold and after a preliminary doze, I lay half conscious, with bones chilled to the marrow laying on the frozen sea ice. Suddenly I was very much awake, aware of the footsteps of a bear just outside the tent. Not sure whether Mike was awake, I whispered my fears to him and we lay there and listened - another creak in the snow, and another. He agreed there was indeed a bear stalking closer and we made the rifle ready by our sides, realising that if it charged it would be on us before the trip-wire did it’s work. The creaks continued spasmodically - the bear was still there and our ears strained to hear it breathing - the only other sound being our beating hearts as we lay there freezing and frightened.

We decided the fear was irrational and we had better sleep but just as we dozed off, another series of creaks re-alerted us to the threat. So the hours passed by until we finally decided that our imaginations had run riot in the darkness and the noises were merely the sea ice cracking under the tent. Thus reassured, we slept soundly until dawn but on reflection, it amuses us that we were not concerned about the ice cracking underneath us. Only polar bears loom large in the wild dreams of Arctic adventurers.

To cut a long story short, our attempts to reach our destination were thwarted by impenetrable pack ice and open water, so we had to hunker down on a neighbouring island in the hope the sea would refreeze.

We sheltered in a small cabin that had to be repaired before we could live there because a bear had vandalised the front wall. But when we’d dug out all the snow and ice and rebuilt the windows, it proved quite cosy. However, bad weather meant we had to waste seven days there and the clock was ticking. If we were to capture the film we needed before all the bears left their dens, we needed to move fast.

.jpg) |

| after a long search, we were tired and defeated by the impassable gaps in the ice |

Desperate, we chartered a large helicopter to carry all our skidoos, camera gear, fuel and food supplies across the open water to Edgeoya so that we could commence our search. When we landed at Kapp Lee we found ourselves thwarted once again, for a bear had broken the substantial door of the cabin and left it slightly open. No problem you might think, but the gap had allowed snow to blow in and fill the area behind - this had then frozen. All we could get through the gap was an arm, but after two hours using an ice axe to chip away, we were no nearer opening the door. The wind was now blowing hard, we were cold and hungry and darkness was closing in, so we reluctantly broke in through the window, then cut the ice away from the door from the inside.

Once we’d entered, we were relived to see that the bear had not wrecked the sleeping accommodation and after a ten day journey we were finally set up to start work in earnest - we had lost valuable time but were in good spirits. It was my lucky turn for the top bunk - warm air rises - and as I snuggled down, I noticed the scratches of a previous visitor in the ceiling. It was the great claw marks of a bear, a true “who'se been sleeping in my bed moment.” I had sweet dreams that night.

14th March was foul, blowing hard from the north, the air now very cold, and the comparatively warm sea-water steamed, so it was a good time to test the camera gear and remove some of the snow from inside the hut. We planned to divide into two search teams to improve our chances of finding bear dens but we now had a fifth team member because an arctic fox had befriended us and with half an hour was inseparable. We called him or her ‘Lief’, and it soon learned that responding to that name resulted in a reward of a few raisins or bits of biscuit. Lief became hand tame in a few minutes - foxes have to exploit every food source if they are to survive the extreme cold and he became a charming mascot throughout our stay.

In fact, it was he who maybe saved our lives, for when distracted as we packed our sledges for a camping expedition next day, with Lief on the boxes searching for hand outs, he suddenly fled with his tail between his legs.

Spinning round, we saw a large bear marching purposefully into camp, so Mike rushed into the hut for a thunder flash and rifle while I leapt behind the skidoo for cover. This sudden burst of activity frightened the bear and it fled off over the ice as fast as it had approached. Lief returned and was rewarded with extra raisins for alerting us to the danger.

It’s tempting to brag about the dangers of working with polar bears to show how brave we were, but to put it in perspective, our scientific consultant and leading authority on polar bears Dr. Ian Sterling of the Canadian Wildlife Service has worked closely with bears for twenty six years and never had to shoot one. However, as all the stories we’d been told confirmed, there are certainly risks, so being family men, we were armed to the teeth with rifles, magnum pistols, flares and thunder flashes. In fact, the locals joked that we probably had more firearms than the Norwegian army!

God forbid if we ever had to harm a bear for a mere TV show, that would be unforgivable, so we’d been told how to minimise the risks and distract them if and when they approached, giving us time to retreat to a safe distance. In fact, having started with an underlying fear of the bears, I grew very fond of them over time and would let them get very close so my film shots were as striking as they could be. They hadn’t invented ‘Health and Safety’ in those days but I still dream about them, even after nearly forty years!

|

| searching routes for the northern half of the island and sites of den failures |

|

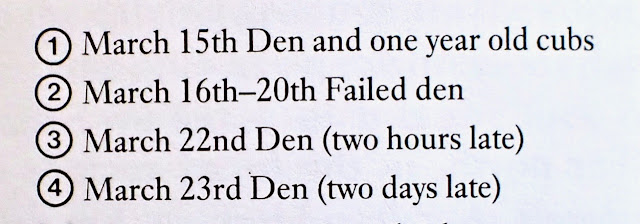

| our failure list |

Anyway, back to the search for bear dens and the next three weeks were as frustrating and disappointing as any filming could ever be. Both teams were finding the occasional bear den but these were either one year olds sheltering with mum from the storms, failed breeders or worse still, we were just too late, one family having left only two hours before we found their footprints. Soon after, we found another den, and this entry in our book describes our feelings of despair …

‘Next morning we’d had no sighting of the bear, so Rasmus went up the mountainside to the hole and discovered that it had indeed been a maternity den, though female and cubs had left maybe two days before.

|

| too late - Rasmus just above one of the dens - it's a searchers nightmare |

|

| skidooing into an ice crystal double sun |

We had covered 228 kilometres in four days and seen just one bear, but on the way home we met two big males, one a really superb animal who stood on his hind legs and towered above us as we approached, then baked off into the pack ice. The other suddenly surprised us on a ridge just above the skidoos. He was blooded and determined and we wondered if he had fought with the other male.

Such fights can be vicious if the prize is a female in heat. He followed us and had to be dissuaded with two flares. But each time he came forward again and in the end it was us who had to back off!

Within half an hour we were back at Kapp Lee. Perhaps it was one of those big male bears that woke us at 5.30 a.m. by banging into our trip wires, but at least he ran off.

Next day, apart from the delight of a thorough wash, we had some hard thinking to do. It was already the 25th March and we had taken very little film. Time was running out. We had searched all the areas on the northern part of the island and the only place we had not ventured was the southern part, very remote from base camp. So it was with a mixture of reluctance and trepidation that we headed south with seven days’ supplies and a sledge load of fuel.

The journey was extremely difficult, for it was very windy, creating not only extreme cold, but a complete white-out. We all used compasses but, even though on exactly the right route through the mountains, we nearly plunged to our deaths into a crevasse which lay hidden in our path. Rasmus was leading and suddenly had a sixth sense there was danger ahead. He signalled us to stop immediately and saved our lives. After that we collected the black droppings of reindeer and I walked in front of the leading skidoo, throwing the black markers ahead. If the dropping disappeared, there was a precipice or crevasse. Thus we made slow but safe progress and eventually crossed over the mountain pass.

After that narrow escape, the rest of the journey was long but easy and we were delighted to find the cabin at the southern end had not been wrecked by bears, though the sight on opening the door was stunning. Every surface, tables, chairs, books and bunks were covered in several centimetres of hoar-frost. It looked like a fairy-tale scene from a movie and it seemed appropriate that the hut had been christened ‘Permafrost City’.

With numerous logs available on the nearby shore we soon changed the interior from Arctic chill to tropical damp, but by next morning the Arctic had lost some of it’s glamour, for the temperature had dropped to -31ºC, and during the next ten hours of searching, the cold wind was almost unbearable, with frostbite threatening nose, face and fingers and watering eyes freezing up.

But at 4 p.m. we thought our luck had finally changed, for we found a mother and cub on a snow slope above the sea ice. The cub was playing, climbing up the steep hill and sliding down, colliding with its resting mother. I stalked closer, using an iceberg for cover, then just as I was in position for some good film, mother and cub fled onto the sea ice. I was downwind and found her departure difficult to understand when suddenly the skidoos of Mike and Birger appeared round a bluff. They had been searching areas ten kilometres to the north and failing to find anything, had appeared at the worst possible moment. It was the cruellest bad luck, and with such unbelievable coincidences apparently stacked against us, I lost heart, and for the first time in four difficult weeks started to believe we might not succeed in filming a bear with cubs after all.

However, 28th March was a new day, and by facing adversity comes triumph. After Rasmus and I had searched all the likely terrain on the coldest day so far, with the temperature at minus 34ºC, we headed along the sea ice to the most southerly tip of Edgeoya and just as Rasmus was gazing out to sea, dreaming perhaps of his far off Norwegian homeland, my heart lept with joy, for there above us was a polar bear den. A large plug of snow lay by the entrance, and fresh tracks led 30 metres down the slope, then back up to the den.

We shook hands and smiled with joy, then remembering all the other disappointments, tempered our enthusiasm by thinking the worst. Surely a female would not have cubs in such a dangerous spot as this, close to the sea ice where numerous male bears would be hunting seals. No, it was more likely to be a temporary den as bears do ‘hole up’ for two or three weeks, to rest or weather a storm.

However, we couldn’t be sure, so built a snow shelter out on the sea ice for filming, about 100 metres below the den. As we did so, a head appeared and watched us briefly, but there was no further sign of her and we pulled out at dusk, anxious to return as soon as there was enough light to skidoo back at dawn.

We rose at 5 a.m. to a beautiful clear dawn. It was now minus 37ºC but we urgently rushed towards the den, afraid of missing the female, in case she chose to leave on such a fine morning.

As we approached she did leave the den, walking down the hill before investigating our ice hide. She sniffed around, climbed in through the gap we’d left in the back, found the thunder flash we had left in a crack and eat it, then inconsiderately crashed through our front wall! Even more disturbing was the way she failed to return to the den but instead headed out onto the pack ice. It had been a temporary den after all, and now, used to these setbacks, we grabbed the camera and set off in rapid pursuit to film her activity.

Our disappointment at yet another useless den changed to happiness when a large male bear appeared in a mirage and as he walked the frozen sea in search of seals, we were able to film the female giving him a wide birth. Then they both drifted off into the haze.

Returning to our hide to inspect the damage, I suddenly became aware that we were being watched, and looking up at the den, saw a bear’s face blinking at us in the bright sun. It was a large female, so the other bear had been a visitor and we were still in business. We dived into the remains of our snow hide but had to wait until mid-afternoon before her head appeared for just a few seconds. By then the sun had gone and the wind further chilled us. We had been out on the sea ice, filming for ten hours in minus 37º C.

However, we had taken the precaution of doing an Arctic survival course before venturing north and one message the Marines had stressed was “Cold Can Kill”. They also taught us how to read the signs of hypothermia: drifting concentration, uncharacteristic behaviour, shivering, stumbling, defects of vision and unconsciousness, [normal for me now at age eighty, but not in 1984!]. Sitting still all day in an ice hide had taken me to hypothermia stage three and I was in trouble, so we reluctantly abandoned ship and motored rapidly home to our cabin where I climbed into my sleeping bag with a hot drink and slowly thawed out. I was really cold, but within a couple of hours some warmth had returned to all except my hands and feet, and I slept soundly.

Next day the female’s head appeared just twice in ten hours of waiting, but at least she looked relaxed and we still hoped she had cubs. Just in case we had got it wrong yet again, Mike and Birger continued searching other valleys for alternative dens.

31st March was once again cold, clear and crisp - a beautiful spring day, and as if in response to the sun, the female appeared at 9.30 a.m. and immediately climbed out of the den. She yawned and stretched and her joy at release from four months entombed in an ice cave seemed very evident. She slid down the mountain towards us on her back, head wallowing in the powder snow, legs waving in the air. She rubbed her back to and fro, then rolled on to her front and rubbed her belly, eventually stopping her rapid descent by pushing her huge paws in front and snow-ploughing a deep furrow.

It was a wonderful bit of film but I wasn’t sure I'd filmed it correctly because my eye had iced up and so had to rely on my instinct as the bear slid towards the camera. What’s more, we wouldn’t know if I’d judged the focus correctly until we were back home in England.

Our star looked very thin, a sign she did have cubs, but when she came down onto the sea ice in front of us and disappeared to the north until only a speck, we really felt in more despair than ever before. Rasmus had never seen a mother travel far from a den in which she had cubs and our female was now four kilometres away.

We just sat in silent prayer and waited and, as if somebody up there loved us, the female did finally turn round and within three hours was back in the den. It had been a long three hours!

In the afternoon she popped out again, briefly, and there between her legs was a cub. Rasmus and I danced a discreet jig, shook hands, hugged and screamed silent cries of triumph. The sense of elation was intense, and though she didn’t appear again that day, we felt sure we would finally capture our vital sequence. We celebrated with Mike and Birger that evening, then watched a large male bear walk past the cabin in the twilight of an Arctic night. Life felt wonderful again.

Next day was the 1st April. What twists of fate would play their hand today we thought, conjured by some evil troll? Surely we cannot be sure of succeeding even now? But another wonderfully calm, sunny day gave us a chance and at about 8.30 a.m. the female appeared, blinked briefly in the bright light, then climbed out and sat by the den entrance. A cub soon appeared, then another, and as Mum walked amongst them I felt sure I saw a third. Within moments it was confirmed; there were three cubs, a most unusual phenomenon, for one or two cubs are more usual. So lady luck had at last turned in our favour.

The smallest cub was hardly the size of a little terrier, whereas the other two were a more normal dumpy dog size, and quite white, certainly paler than their rather yellowy-white mother. Their first sight of the outside world was greeted with terrified squeaks as they looked down the steep mountainside with trepidation. The den was about 150 metres above the sea ice, and somehow they had to get down. The female fussed over them, then walked a few confident paces down, whilst two of the cubs followed gingerly, sliding backwards, with claws clutching the snow. The other stayed in the den entrance and cried so loudly that the female returned and suckled all three in the sun.

They slept for an hour, then clambered up and down the slope, slowly growing in confidence before returning to the den. We hoped they would be around for what is normally two or three days so I could film the cubs playing and suckling, but at 2 p.m. the female emerged purposefully and started down towards the sea ice, followed protestingly by the little cubs. Perhaps she realised how vulnerable they were in this spot, for they had already been visited by two bears and probably seen others too. Or perhaps she was really hungry, for she hadn't eaten for four months and suckling three cubs must have placed great demand on her reserves. Whatever the reason, her determined move out onto the sea ice was a last disappointment, but we followed discreetly on foot, and interspersed with sleep and suckling, the family were soon three kilometres from the shore and deep into the cover of the pack ice.

Among the chaos of ice blocks she would probably be able to hide the cubs from marauding male bears, and she was now in the realm of the seal, and within sight of her first meal. We bade them a fond farewell and watched their departure into a white haze, feeling very sad it was all over.

We had travelled 8,000 kilometres to capture about ten minutes of edited film; that is about 500 kilometres sledging per minute; we hoped the audience would feel it was worthwhile. And as for us, we had seen the Arctic at its best, and its worst, for it had been a tough but exhilarating trip. It was an adventure that few others could ever hope to experience and every moment, however cold, however difficult or depressing, even dangerous, now seemed worthwhile. It had been a rare privilege to share that remote island with the bears, and we knew how lucky we had been.

As for the audience with whom we shared our adventures, the three one hour films went down a storm and even won us six British Academy Award nominations, along with, rather bizarrely, a medal from the Royal Geographic Society for exploration. I suppose we qualified by travelling to places that other folk had never been to, but it was a pleasant surprise for us adventurous film makers.

As for the film of the mother bear sliding down the mountain on her back that I couldn’t see due to a frozen eye, I did get lucky and follow the focus correctly. What’s more, the scene became a fixture for many years in the BBC’s ‘highlight reels’, so it was always nice to be reminded of that magical moment, shared with our lovely polar bear and her cubs.If you have the patience to read more of our book 'Kingdom of the Ice Bear' ... for what I've included are just a few excerpts, then I would imagine your local library might find a copy. It was translated into three languages and was in The Times best seller lists for several weeks, so there must be a few copies around.

In the meantime, Sue and I wish our readers a rewarding and happy Christmas and hope that life is kind to you all next year.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)