FRIENDS FOR LIFE

With the rain hammering down outside, I feel it’s an ideal time to write a happy story about my schooldays friend, Kevin Hawkes.

But how did we meet? Well, when I was a youngster, my Dad was the conductor of the Yorkshire Symphony Orchestra, and because music was in my blood, I won a scholarship to sing in the choir of the magnificent cathedral at Ely. So in 1951, at age eight and a half, I was sent away to the King’s School to earn my keep. I remember a friend once asked me, "Didn't your parents love you?"

Our singing in such a spectacular building was inspiring, even if intense, with choir practice and choral evensong every day except Tuesdays and with the added burden of rehearsals and matins on Sunday mornings, there was little time to be lonely. The disciplined work helped me to recover from the shock of being alone and away from home for much of the year, though I soon learnt to love the flat Fenland landscapes and this inspiring ‘land of skies’.

School work, music and sports filled most of the days, so time to escape into the great outdoors and admire the abundant wildlife that enhances every corner of these beautiful wetlands was scarce.

However, encouraged by my grandfather and the old fly rod and reel he gave me, I soon became a keen fisherman and being out there by the river Great Ouse, I marvelled at all the birdlife and the fishing potential. In those days, it was everywhere!Friends are always precious, especially when away from home for long periods, their loyalty and trust so important when sharing common interests. I treasure all the friends I’ve been blessed with over many years at home and abroad and try to keep in touch with them all, sharing some of my life while living in the wilds for months at a time. However, I lost touch with one special school friend when I left in 1961 and his whereabouts remained a mystery for the last sixty plus years, though how he became my main school pal is also a mystery. I guess we were both inspired by the Fens when sharing the birding and fishing and he seemed to be beside me so often that we became what might now be described as ‘soul mates’.

Kevin was as keen as I on those boyhood pursuits, though he was only known to me at school by his nickname ‘Purdy’. Mine was Luty [don’t ask], and because of our passion for wildlife, we became known for being capable bird vets, so the Ely locals would bring us any injured birds for care.

On one memorable day, two tawny owls chicks were brought to us. They had fallen out of their cathedral tower nest, so Purdy and I spent many weeks raising them in the school garden. At night we kept them in the rugby boot store, though our rugby team weren’t too enamoured when they found coughed up owl pellets in their rugby boots!

This is Purdy with our pair of lovebirds, observed one day in their roosting bush, beak rubbing and murmuring affectionately to each other, so we named them Archibald and Susie.

We became very fond of them and they trusted us too, so after several weeks they learnt how to fly, spending the day in a giant beech tree in the school grounds and magically, when we called them in the evening, floating gently down to take food from our hands, clicking their beaks in delight at the school dinner left overs, an unforgettable privilege.

Among others, we also nursed back to health a jackdaw with a broken wing, a delightful pet while he healed before eventually flying free, so effectionate as he nibbled our ears.

We had other birding adventures too, cycling round the Fens trying to find as many owl nests as possible. Almost every field was lined with ancient willow trees, pollarded for making baskets and eel traps, so they were knarled and offered many cavities for hole nesting birds such as jackdaws, stock doves and our most sought after barn owls.

We took to mapping their nests, counting their eggs and even pencil marking them to study their age related hatching. On several occasions, the incubating female would refuse to get off her eggs, so armed with a bent spoon on a stick, we would very carefully lift her to one side so we could count her clutch. She would be annoyed, clicking and hissing at us, though as soon as we’d finished our attempts at ‘scientific’ analysis, she would shuffle back onto her eggs and continue incubating.

We also found young stock doves which were measured and returned unharmed of course and tawny owl nests in the large elm trees and ancient oaks but never tampered with them due to their reputation for attacking humans. The famous bird photographer Eric Hosking was a victim of a particularly feisty tawny that he was photographing and lost an eye when it attacked him, the consolation being that this provided him with the perfect title for his autobiography, “An Eye for a Bird”.

Fishing of course provided us with lots of birding opportunities, though initially our favourite fishing spot was beside the Cutter Inn in the centre of Ely. This is where a small drain ran into the Ouse, the protecting wall providing a smooth well polished seat to sit on as several of us lads dangled worms and bread for the perch and gudgeon and if we were lucky, small roach. My wife Sue and I revisited Ely and the old school a few years back and the ‘Cutter Inn’ is still there, the well polished wall now replaced by a footpath. The spot was being fished by young lads as we watched and will no doubt provide happy memories for them too. It certainly does for us, especially as when fishing there with Purdy one day, I cast out much further than normal to an old weed covered wagon wheel and baiting with a big lump of flake, caught a large roach. It was all of ten inches long and a monster for us when young so a fire was lit and I’ve been a passionate roach angler ever since.

I had become a disciple of Bernard Venable’s classic book ‘Mr. Crabtree Goes Fishing’ and in it he teaches young Peter how baiting up over several days could attract large shoals of bream. The Great Ouse at Ely is bream heaven, so Purdy and I scrounged stale bread from the school kitchen and chose swims alongside beds of lilies in deep water.

According to Mr.Crabtree, being there at dawn was essential but that created a problem, for we were trapped within the monastic buildings and the large Roman gates called 'The Porta' were always locked at night.Searching diligently, we found one unlocked gate, but that was in the Headmaster’s garden and required us to wheel our tackle laden cycles across his lawn.

Nothing ventured, nothing gained, so stuffing our beds with our pillows so that snooping prefects would think we were sleeping, Purdy and I would rise in the dark and creep out as silently as possible, though how the wheel tracks on the dew covered headmaster’s lawn were never noticed we’ll never know. Or maybe he did see them and cut us some slack? Yes, he might have thought fishing was an admirable hobby for young boys, though I doubt it!

The excitement on finding bubbling bream by the lilies on arrival was unforgettable and we’d fish with large lumps of breadflake under a large porcupine quill. This is the exact float I often used, a bit mouse nibbled now but still effective, and if the swims were mid-river, we’d use a drilled bullet and float-ledger, catching numerous beautiful bronze bream of around three pounds, even up to four pounds if we were lucky, before cycling back to school in time for breakfast. I still love early mornings, even after sixty years, the best time of life by far, with birds singing and the whole day to look forward to.

We were particularly drawn to this deep swim across the river beside the lilies where the swan family are feeding, [now very busy and overgrown] but getting there in the 1950's required us to use a small chain ferry from the rowing club, difficult to operate silently, even in the dark. Knowing no fear, we pulled our way across and so big were the bronze bream that we risked the madness a few more times until, one day, the whole school were summoned to a Headmaster’s meeting, and that means someone was in trouble.

He said, “Would the two boys who have been using the chain ferry on the river please come forward.” Purdy and I looked at each other and shrunk! There was no way we were going to own up and as no-one else knew we were the guilty ones, no boy could tell on us and get us punished, though sadly, we couldn’t fish that bream filled swim any more.

The Roswell Pits where I learnt to sail were an easy cycle ride just to the north of Ely, [it's now a nature reserve], so we fished there for rudd amongst the reed beds and also pre-baited a spot for bream, though this story has a tragic ending.

I had been invited to swim by my cricketing pal John Goodey in the ‘Blue Pool’, a crystal clear and deep blue clay lake at Roswell Pits. Just the afternoon before, the school cricket First Fifteen had remarkably beaten a Cambridge University team and John had made a great catch of their best batsman on the boundary off my bowling, so we were both happily triumphant. However, I declined his swimming invitation because Purdy and I were going to fish our carefully prepared swim, which by then was a jacuzzi of feeding bream. We did catch lots, though they were mainly what we now call ‘skimmers', up to a pound or two.

Upon returning to school in the afternoon, we were told that John had drowned, overcome by cramp and the pal he was swimming with wasn’t strong enough to keep him above water. I was a very strong swimmer and the likelihood of me being able to save him if I’d been there haunts me to this day. It was our first shock of learning how fragile life can be and the school’s cathedral service to honour his passing brought tears to our eyes, even now. However, the adventures with Purdy continued and got more adventurous, cycling off to far flung spots to fish for new species and bigger fish. We had been told by a farmer when searching for owl nests about an old clay pit dug for brick making that contained tench and we badly needed to catch a tench, so one day headed out on a long cycle ride across the Fens to find this magical spot.

As we arrived, nesting redshank and snipe sprang out of the ditches in alarm and hiding our bikes in a hollow, forced our way through the dense brambles and stingers to reveal two pools separated by a thick strip of phragmites, the water surrounded by dense hedges of hawthorn and blackthorn. The delightful cooing of turtle doves filled the air and it is sad to know that all these once common birds have declined so much in just a few years.

The fishing was wonderful, tempered by a relentless deluge of rain, but as tench anglers know, especially as we found this year at the Tenchfishers Masterclass in Surrey, heavy rainfall can certainly turn them on and using small porcupine quills with large bread flake hook baits, we caught about thirteen perfectly plump tench of about two to three pounds.

Fishing doesn’t get much better than that, though it did, for while trying to shelter from the rain in the blackthorn thicket, we disturbed a long-eared owl, the first we had ever seen, so we cycled back to school smelling of tench and very wet, but very happy.

We took it in turns to lower the bait down to them and caught several more before they were spooked and disappeared, but in the years that followed, the lakes produced Rudd of over three pounds, so despite being chuffed with our catch, we had only scratched the surface of these magical lakes. Sadly, those wonderful havens of wildlife are now buried under concrete and named the Cambridge Research Park. Humans call it progress. Winter in the Fens provided another world of wonder, not least the skating when the flooded water meadows iced up and we could ‘skate’ speedily up and down on smoothly slicked runways. We only had wellies while the locals slid for miles on skates.

The fishing had potential too, so Purdy and I started pike and perch fishing, particularly in the Stuntney Drain, for we could usually get a strike or two on spinners from jack pike, our best being a moderate fish of seven pounds. However, on one memorable day I hooked a tench, cleanly hooked in the mouth on a Mepps spinner. It weighed

3lbs 10ozs and because neither of us had ever tasted tench, I whacked it on the head, rolled it in a cloth, stuffed it in the cycle seat satchel and after catching a couple more small pike, we cycled back to school.

Un-wrapping the tench in a sink to clean it off, you can imagine my surprise when having been ‘dead’ for several hours, it wriggled free and splashed us. Whacking it again, then finding our penknives were too blunt to cut the skin, we borrowed a scalpel from nurse and skinned it ready for cooking … and if you’ve never tried eating tench - don’t! Even after soaking in salty water for an hour, it tasted of mud and little else, though you can’t fault those lovely fish for clinging onto life, even when ‘dead’. Tough critters! However, the story doesn’t end there. Purdy and I had returned to Roswell Pits to fish for perch and had success with small roach ‘livelies’, catching several over two pounds to a best of about 2lb 12ozs, and wanting to share our success, I sent the story of our perch success into the Angling Times and as an aside mentioned the remarkable tench of 3lbs 10ozs caught on a spinner. Next week, there it was on the front cover, “Schoolboy lands great catch of perch, topped by a specimen of 3lbs 10ozs” What a shame it wasn’t true.

Purdy and I turned our enthusiasm towards trying to catch a big pike and because it was in those days that Fred J Taylor was proposing the bizarre idea of fishing for pike with frozen herring or mackerel, we had to try it. Roswell Pits had a good reputation for good fish, so it wasn’t long before we were flinging a dead bait as far out as we could, then waiting for action in our old duffle coats in the freezing cold. It was Fred J who spoke those immortal words to Dick Walker “I’ll be glad when I’ve had enough of this!” Though we hadn’t reached that stage to get cold enough when our silver foil indicator rose slowly up to the butt and I struck as hard as my little ten foot rod would allow. The resistance out in the distance was substantial but I remember little of the fight apart from seeing Purdy net our biggest pike to date. It weighed 16lbs and these are pics taken with my box Brownie, the exact swim we caught from above and our splendid catch.Having tried pre-baiting for bream, we reasoned that it might work for pike too, so gathering some scraps of fish from our school dinners, we baited a spot several times just along the bank from our previous biggie and were excited when we eventually lowered our dead fish bait into the spot. The response was almost instant, the float bobbing once before sliding decisively into the depths, so I tightened up the slack and struck into an irresistible force, far more powerful than the sixteen pounder we had caught two weeks ago. The pike simply kept swimming ever faster into the depths and I was powerless to stop it until there was a loud crack when the line parted. That loss of a monster still hurts even now because we’ll never know just how big it was - ever.

How we ever made the time for all our fishing and birding I can’t imagine, for Purdy [No.2 here on the school four] was busy with rowing and rugby and I played in the school orchestra and brass band, sang in our madrigal society and practiced my French horn every day to prepare for my life as a professional musician. I guess our habit of getting up before dawn helped us to win a few extra hours in each day, even if only to do our studies and home work. The birding was always rewarding, even in the Fenland winters, with lots of wildfowl to enjoy, especially when we’d made the long cycle ride over to the Ouse Washes, unknown to all but wildfowlers then but now celebrated as one of England’s most famous birding spots. In those days there were no hides, so we’d just crawl up the flood banks and peer over on our bellies to avoid spooking the flocks.

However, our best duck was seen on the sugar beat factory settlement pools after creeping up the flood bank ‘Red Indian’ style, for there below us was my first ever shoveller and I’ll never forget the excitement of seeing such an exotic looking duck.

I also remember with pain the quirk of Fenland winds, for when cycling out we’d always be facing a head wind but on return, we never enjoyed a tail wind because it had swung 180 degrees and was blowing into our faces - again. It certainly got us fit for our sports!

Purdy and I tried another spot for pike fishing, a long thin pit alongside the railway line, connected to the Ouse and full of fish.

On one memorable day, the pike were feeding voraciously and having caught a few small rudd for bait, every cast was smashed by a pike as it hit the surface and splashy battles commenced. The fish were just jacks up to eight pounds but we caught so many we almost lost count, at least a dozen, providing exciting violence for us both.We reasoned that there must be bigger ones there, so once our school exams were complete, we headed out there and caught a fat and beautiful specimen of 18lbs.I had forgotten my camera and while Purdy held the pike in the edge tied to a rod bag, I cycled the short way back to school for the Box Brownie so that we can admire our catch to this day.

And while mentioning our exams, I passed my A levels, Purdy too no doubt, though the only response I received from the Headmaster upon leaving the school was, “A pleasant surprise”! He obviously thought I was always ‘out there’, birding and fishing, but we did work hard as well as play hard and both enjoyed lots of sport, Purdy rowing for the school, me playing cricket. We also shared our success in the school’s rugby fifteen, winning all our matches one year, bar one draw, thanks to our great coach and history master, John Lund.

I’m the little squirt on bottom left, small but fast and pugnacious. Purdy [in glasses on top right,] was our fearless wing forward and a rugby star, tackling opponents out of the game, flying through the air like an Exocet missile. In the recent Rugby World Cup, the All Black Ardie Savea comes to mind!We both left Kings Ely in 1961 and just moved on in life and as neither of us were followers of the ‘old school tie brigade’, we lost touch. Sue and I often wondered where Purdy was, always hoping that one day we might meet again. We even thought of trying a search, though not knowing his surname, or that he was called Kevin made it impossible. He was just my best school pal nicknamed ‘Purdy’, so when a few months ago we received this letter from Norway, we were excited to find that it was from the man himself. He had found us through our blog and that has got to be the best and only reason for ever writing a blog!

Purdy has been living in Norway for 45 years and this letter included an email address, so we could finally catch up with stories of his life since leaving school. Sue had heard many of our childhood tales about fishing and birding and was most impressed, even surprised that Purdy had vividly remembered the details of our best catches too and as they echoed what I’d told her, she had to accept that the stories were true! Our children Katie and Peter were excited because all the tales I’d told them about our Fenland adventures had made Purdy part of the family, like a brother that I never had. I did have two loving sisters but they didn’t fish! Anyway, via a series of email exchanges I learnt that Purdy/Kevin worked for the Royal Insurance Co, so he had loads of friends and had kept up his sporting prowess by playing lots of golf, so well in fact that his handicap was six. Eventually he returned to his Jordie roots in Tyneside and was covering a large area of Northumberland and all of Durham when he met a Norwegian nurse called Liv and in May ’72 they got married, coincidentally just six months after Sue and I had tied the knot.

By chance, Liv saw an ad. in a Norwegian newspaper for a Matron at an old folks home in Norway, she got the job and they and their three boys packed their bags and have happily lived in Norway ever since.

Their lovely home lies close to this large mountain, the same height as Ben Nevis, so a far cry from the Fens of Purdy’s childhood. He’d given up golf too as there’s not enough flat land!

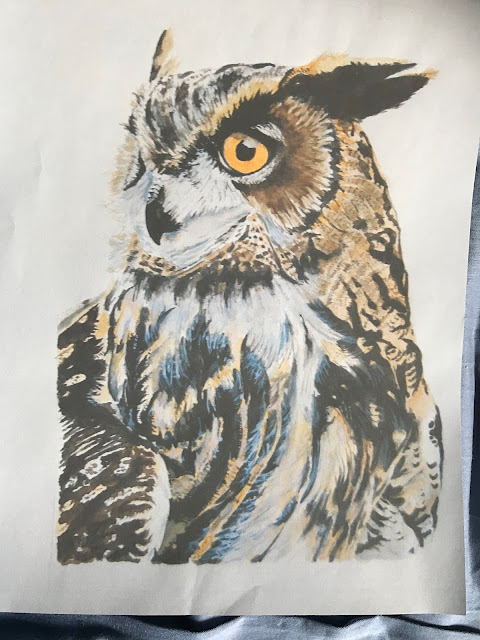

Kevin’s love of wildlife continued, he learn’t to paint and here’s three of his delightful water-colours of an eagle owl, an osprey and a coloured pencil sketch of a barn owl. We are very impressed.

Kevin had always liked painting and once Liv had started running the old folks home, he started painting houses and that included helping a team to paint the largest wooden building in Europe, the impressive and beautiful Kviknes Hotel alongside Sognefjord, seen below. That's a lot of painting!

Now freelance, he eventually built their own home in Kvammen and had a roaring business enjoying restoring old wooden buildings when a bombshell struck. He was diagnosed with primary progressive MS. It was not too bad at first but became worse after the Covid crisis, a cruel blow for anyone, but particularly for such a sporting and active father.

The family had a single story house built that allowed Kevin to continue his creative work, including these remarkable cross-stitch

marvels, one of a carpet market ...

the other a ‘work in progress’ of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. I reckon that Michelangelo had an easier task painting it than Kevin had stitching it, tho' I'm guessing that he too will have to lie down when it's completed!

It strikes us as remarkable that Kevin, in spite of his handicaps, still has the patience and determination to be so creative and so it felt appropriate that I should share one of my creative results since leaving schooland sent him a copy of our BBC series, ‘A Passion for Angling’ in the hope that he might appreciate re-visiting UK fishing.

He enjoyed our adventures, though I'd forgotten to tell him that Peter in the first programme was in fact our son, so I was delighted to learn that Kevin's youngest son is also a keen angler and he enjoyed the film’s stories even if surprised by the ancient tackle that Mr. Yates was using. It’s as if Kevin and I have come full circle and if you suspect I've been seeing our schooldays together through rose tinted glasses you'd be wrong, because the 'good old days' were in fact good because we made the most of our opportunities, even if the school wished we hadn't and had spent more time studying! In spite of choosing not to be academics, Kevin and I have done OK, so I hope and pray that we will still be exchanging stories of the past and present and sharing his art, long into the future.

Friends for life. Yes, most certainly.

.jpg)